Я могу часами говорить про “Молчание ягнят” , но сейчас бы хотел сфокусироваться на одном аспекте — про то, как хитроумно и круто фильм работает с субъективностью взгляда (грубо говоря, чьими глазами и как мы смотрим на происходящее в фильме). Сухой медицинский факт про сюжет:одна из основных сюжетных линий «Молчания» — про то, как молодая стажерка ФБР Кларисса Старлинг расследует серию убийств и параллельно продариается через враждебный для нее мужской мир.

Противостояние с миром мужчин несколько раз прям довольно очевидно показано визуально, как например, в сцене с лифтом:

Или почти во всех сценах с ее обучением в ФБР: (Джонсону — похвала, Клариссе — разнос) (Буквально визуальная метафора того, как Старлинг приходится по кругу отбиваться от мужчин) Или вообще, не стесняясь, окидывают оценивающий взглядом: Но ловче всего фильм это подчеркивает игрой с мужским взглядом камеры.

Из-за этого взгляд камеры в кино (то, как мы смотрим на происходящее) — он мужской (male gaze). Поэтому и мужчины, и женщины, и события в кино чаще показываются с мужской точки зрения.

Конец минутки синфельского занудства. Так вот, «Молчание ягнят» переворачивает эту теорию наоборот.

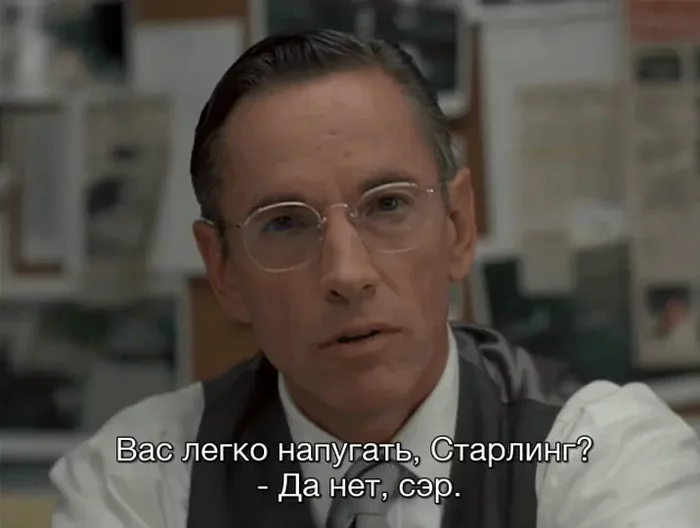

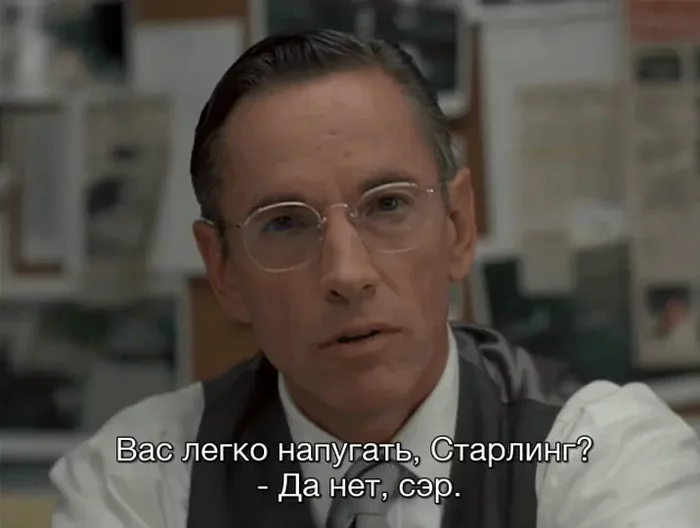

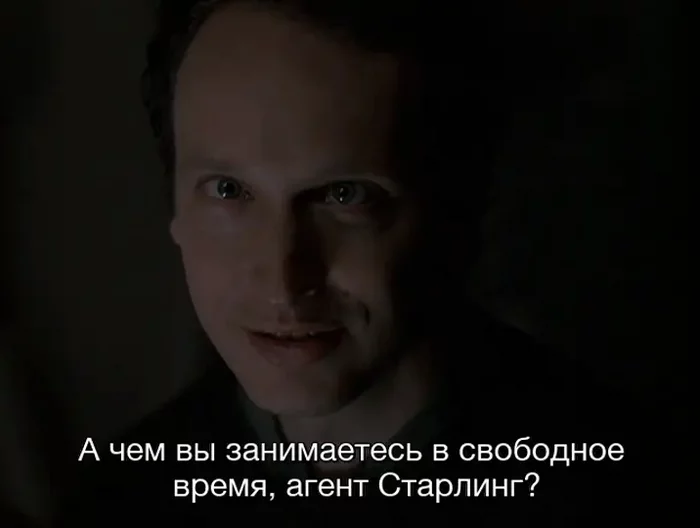

Если обычно зрители смотрят на кино из позиции мужского взгляда — то в «Молчании», буквально, само кино смотрит на зрителя этим самым мужским взглядом, заставляя чувствовать себя максимально неуютно. Чаще всего это проявляется в сценах диалогов.

Они устроены так, чтобы мы максимально близко идентифицировали себя с Клариссой. Обычно в кино, говорящий смотрит чуть-чуть за камеру.

Каноничный пример геометрии взглядов из “Криминального чтива”:

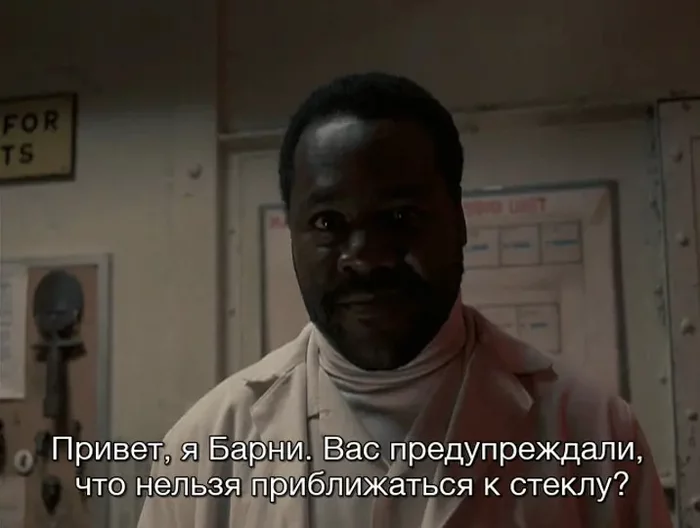

Ну или диалог снимают классической восьмеркой, где лица говорящих разведены по разным углам кадров. В «Молчании» же все не так — персонажи, когда говорят, смотрят прямо в камеру — то есть буквально на нас (причем обычно еще с более близкого ракурсе, чем следовало бы).

Чтобы мы прям чувствовали себя на месте неопытной и молодой стажерки ФБР. Ну а вишенка на торте — одна из моих любимых сцен, с шерифами в комнате, когда камера делает круговой пролет.

И мы буквально ощущаем на себе это некомфортное мужское пристальное внимание. Весь этот дуализм мужского-женского также отчетливо проявляется в противостоянии Клариссы и Буффало Билла.

Девушка Кларисса хочет занять полноценную мужскую роль, а мужчина Буффоло Билл — напротив, женскую.

В фильме есть только один субъективный взгляд помимо взгляда из позиции Клариссы — и это тогда, когда мы смотрим на жертв глазами Буффало Билла. При этом маньяк настолько объективирует женщин, насколько это вообще возможно — они как вещь, нужны только как источники материала (он даже не называет жертв по именам, говоря о них в третьем роде).

Таким образом, получается контрастность — в сценах Клариссы камера смотрит взглядом молодой девушки, в сценах с Биллом — мы смотрим взглядом маньяка на этих самых молодых девушек. А кульминацией тут выступает финальная сцена.

Это переосмысливание тропаFinal Girl(где в слэшерах в конце обычно остается одна девушка, которая героически отбивается от супостата ножом или чем-то подобным). Только снова первертыш — обычно в ужастиках мы смотрим из позиции жертвы, а тут мы смотрим глазами маньяка.

Ну и символизм сцены — для того, чтобы победить, Клариссе необходимо буквально почувствовать на себе этот самый мужской взгляд (исходящий от нас, от зрителей) — что она и делает. ## Про другие визуальные приемы Также хочется отметить то, как оператор работает с приближением.

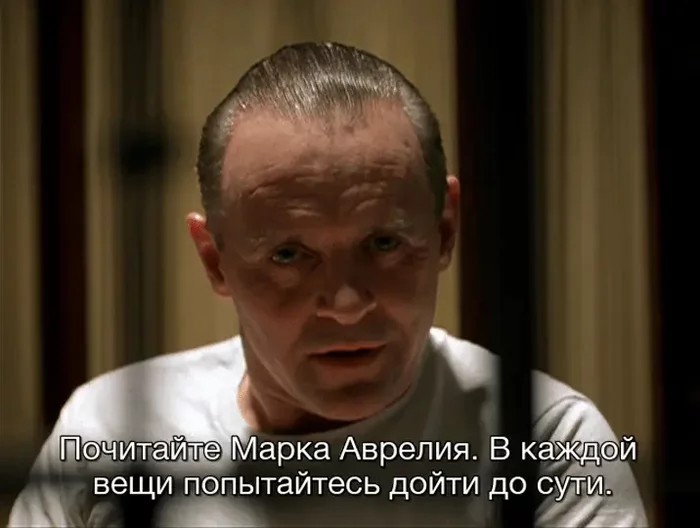

Это особенно видно, в последней сцене диалога Ганнибала и Клариссы (всё таки невозможно написать статью про “Молчания” без упоминания Лектера 🙂) Со временем диалога лицо Лектера настолько приближается к нам, что мы уже даже не видим прутьев решетки.

Про взгляд прям нам в душу, чтобы было некомфортно я уже повторяться не буду :) Ну и напоследок— мне всегда очень нравилась метафора вот этого кадра из финала:

На мой взгляд, пушистая белая собачка, которая находится в руках у спасенной девушки — это как раз образ тех самых овечек из кошмаров Клариссы. Которых Старлинг не смогла спасти в детстве, но которых смогла спасти сейчас.

И собачка в финальном кадре уже спокойно молчит. Спасибо за прочтение!

I could talk for hours about “The Silence of the Lambs”, but now I’d like to focus on one aspect — how cleverly and brilliantly the film works with the subjectivity of gaze (roughly speaking, through whose eyes and how we look at what’s happening in the film).

A dry medical fact about the plot: one of the main plot lines of “Silence” is about how a young FBI trainee Clarice Starling investigates a series of murders and simultaneously breaks through the hostile male world for her.

The confrontation with the world of men is shown quite obviously visually several times, for example, in the elevator scene:

Or in almost all scenes with her training at the FBI:

(Johnson gets praise, Clarice gets a dressing down)

(Literally a visual metaphor of how Starling has to fend off men in circles)

Or they just don’t hesitate to give an evaluating look:

But most cleverly, the film emphasizes this by playing with the male gaze of the camera.

There’s a theory of the male gaze (part of a powerful essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”).

There’s a fairly simple thought there — most films are made by men (directors, cinematographers, screenwriters), men mainly play the leading roles, and men mainly watch them.

Because of this, the camera’s gaze in cinema (how we look at what’s happening) — it’s male (male gaze).

Therefore, both men and women, and events in cinema are more often shown from a male point of view.

End of cinephile pedantry moment.

So, “The Silence of the Lambs” turns this theory upside down.

If usually viewers watch cinema from the position of the male gaze — then in “Silence”, literally, the cinema itself looks at the viewer with this very male gaze, making them feel extremely uncomfortable.

This most often manifests itself in dialogue scenes.

They are structured so that we identify ourselves as closely as possible with Clarice.

Usually in cinema, the speaker looks slightly past the camera.

Canonical example of gaze geometry from “Pulp Fiction”:

Or dialogue is shot with a classic figure-eight, where the faces of the speakers are separated into different corners of the frames.

In “Silence” it’s all different — the characters, when they speak, look directly at the camera — that is, literally at us (and usually from a closer angle than it should be).

So that we literally feel ourselves in the place of an inexperienced and young FBI trainee.

And the cherry on top — one of my favorite scenes, with the sheriffs in the room, when the camera makes a circular flight.

And we literally feel this uncomfortable male intense attention on ourselves.

This entire male-female dualism also clearly manifests itself in the confrontation between Clarice and Buffalo Bill.

The girl Clarice wants to take a full male role, while the man Buffalo Bill — on the contrary, a female one.

There’s only one subjective gaze in the film besides the gaze from Clarice’s position — and that’s when we look at the victims through Buffalo Bill’s eyes.

At the same time, the maniac objectifies women as much as possible — they are like a thing, needed only as sources of material (he doesn’t even call the victims by name, speaking about them in the third person).

Thus, there’s a contrast — in Clarice’s scenes, the camera looks with the gaze of a young girl, in scenes with Bill — we look with the gaze of a maniac at these very young girls.

And the culmination here is the final scene.

This is a rethinking of the Final Girl trope (where in slashers at the end there’s usually one girl left who heroically fights off the villain with a knife or something similar).

Only again a twist — usually in horror films we watch from the victim’s position, but here we watch through the maniac’s eyes.

And the symbolism of the scene — in order to win, Clarice needs to literally feel this very male gaze on herself (coming from us, from the viewers) — which she does.

About Other Visual Techniques

I also want to note how the cinematographer works with zooming in.

This is especially visible in the last scene of the dialogue between Hannibal and Clarice (after all, it’s impossible to write an article about “Silence” without mentioning Lecter 🙂)

Over the course of the dialogue, Lecter’s face gets so close to us that we can’t even see the bars of the cell anymore.

About the gaze straight into our soul, to make it uncomfortable, I won’t repeat myself again :)

And finally — I’ve always really liked the metaphor of this shot from the finale:

In my opinion, the fluffy white dog that’s in the rescued girl’s arms — that’s exactly the image of those very lambs from Clarice’s nightmares.

Which Starling couldn’t save in childhood, but which she was able to save now.

And the dog in the final shot is already calmly silent.

Thanks for reading!

My Telegram channel (post taken from there): t.me/odno_kino