In the 2000s, Bob Ferguson (Leonardo DiCaprio) is an explosives expert for the leftist terror cell French-75. The group breaks undocumented Mexican immigrants out of detention camps and plants bombs (timed to explode after closing) in banks and government offices.

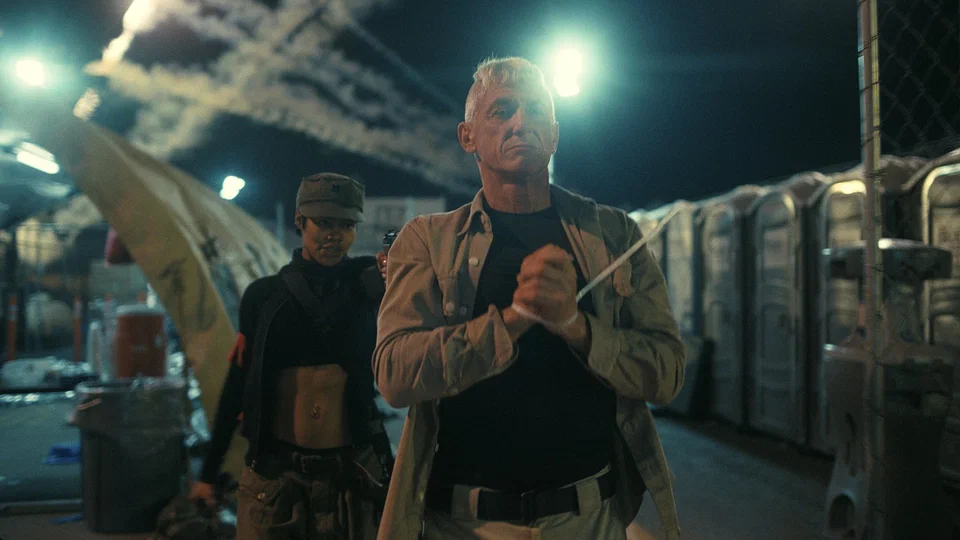

He falls into a torrid relationship with fellow fighter Perfidy Beverly Hills (Teyana Taylor). But the unstoppable Perfidy keeps another man awake at night — fascist Colonel Lockjaw (Sean Penn), who wants to arrest her, bed her, and soon manages both.

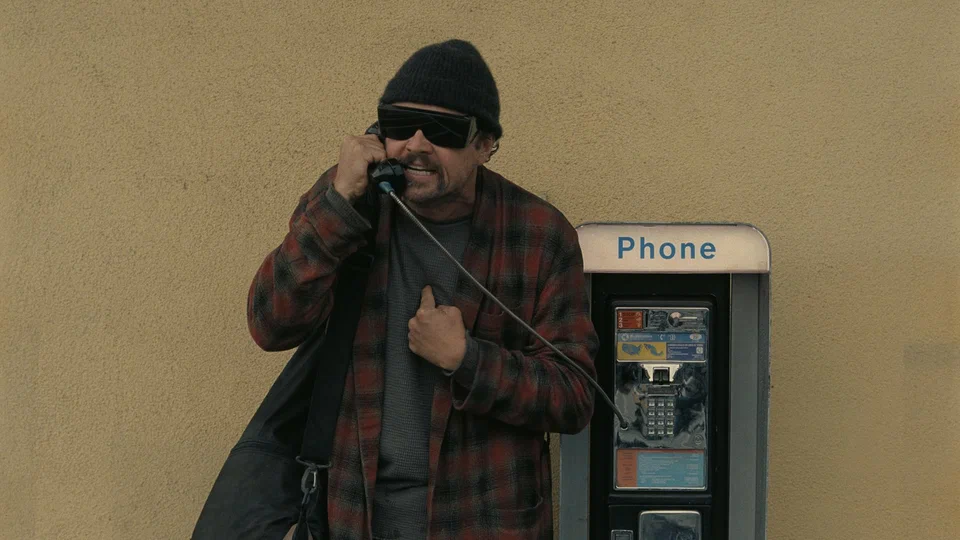

Perfidy has a daughter (who the father is remains unclear), French-75 collapses, and Bob escapes with the baby to Bacton Cross, a predominantly Latino town in Southern California. Sixteen years later he’s still hiding there, smoking mild weed and forbidding his daughter Willa (Chase Infiniti) to use a phone — until Lockjaw finally tracks them down.

“Battle After Battle,” Paul Thomas Anderson’s tenth feature, is now rolling out internationally. Part pitch-black comedy, part topical political satire, part action movie, it follows a leftist militant on the run (DiCaprio) trying to save his 16-year-old daughter from a racist colonel (Penn) who might be her biological father.

Anderson’s anniversary project is unusual on several fronts. It’s by far his most expensive film; he has handled large budgets before, but never blockbuster numbers (“Battle” is estimated at a minimum of $130 million, with twenty of that reportedly going to DiCaprio). It’s also the first Anderson film that can, with some caveats, be called an action movie (though we all remember Adam Sandler’s scrap with Philip Seymour Hoffman’s goons in “Punch-Drunk Love”).

The most intriguing shift is elsewhere: the director famed for retro obsession suddenly made a scaldingly relevant story — not just about today, but a bit about tomorrow. The basic setup borrows from Thomas Pynchon’s novel “Vineland,” about hippie radicals in the Reagan era. Anderson already explored that clash between the 1960s and the incoming 1980s in “Inherent Vice,” so this time he updates it to 21st-century conflicts. Considering the production schedule, he wasn’t chasing the news cycle — he was predicting it. And he nailed it: news footage of National Guard patrols in L.A. or ICE raids could be spliced directly into the movie. Maybe, finally, the leading American auteur will get a couple of long-overdue Oscars; plenty of people (prematurely, perhaps) are betting on it.

The one person certain to land at least a nomination is Sean Penn, who takes an already cartoonish villain and pushes him into territory where disgust gives way to more complex feelings. Lockjaw, with his precious uniforms, odd gait, and tangled sexuality, dreams of joining the secret society “Christmas Adventurers,” a powerful Protestant racist lodge that controls business and politics. Having a daughter with a Black woman destroys his prospects, which is what sets the plot in motion. But the conflict with Lockjaw is metaphorical too. The revolution, embodied by Perfidy, arouses him so intensely (Anderson, who never ignores penis jokes, certainly doesn’t skip the topic of erections here) that a near-Greek-tragedy dilemma emerges: what if the colonel himself fathered the next revolution in the form of young, furious Willa?

Willa’s de facto father is Lockjaw’s polar opposite. No Nazi haircut, just an unkempt ponytail; no tight uniform, just a threadbare robe that he shuffles around in like the Dude (they’re also united by their fondness for various substances). Bob doesn’t resemble Rick Dalton, yet DiCaprio taps the same gangly comic charm Quentin Tarantino discovered. He never hogs the spotlight — plenty unfolds without him — and still the paranoid pulse in “Battle” is mainly his. A hysterical sequence where he dials a clandestine number but can’t remember the password because he literally smoked that part of his brain away years ago feels almost on par with the trailer meltdown in “Once Upon a Time in… Hollywood.”

Bob was once a legend of the armed underground, but after 16 years on the couch rewatching Gillo Pontecorvo, life has raced ahead — something he notices with equal parts grouchiness and wonder. The Latino neighbors quietly assembled a far more effective resistance than French-75 ever had (the name, by the way, comes from a cocktail; Anderson inherited Pynchon’s love of goofy monikers and maybe cast Chase Infiniti for the same reason). Benicio del Toro gets a very funny turn as an imperturbable sensei who trains Willa in martial arts and rescues Bob when things get hairy.

Anderson’s action scenes — mostly chases — are unsurprisingly glorious. He constructs them differently than genre specialists, yet the suspense and spectacle are impeccable, whether it’s rooftop pursuits or a near-surreal duel between cars on a desert highway that ripples like waves to Jonny Greenwood’s nervous percussion. Michael Bauman, who shot “Licorice Pizza,” used widescreen VistaVision film stock, a format enjoying a renaissance after “The Brutalist.” Beyond the movie’s routine sheen, “Battle” features flashes of staggering beauty: heavily pregnant Perfidy blasting away with an automatic rifle — the striking poster image — finds a bittersweet rhyme later with a similar shot featuring her daughter.

Anderson’s attitude toward the film’s many revolutionaries — from hipsters to nuns — is deliberately ambiguous. The movie could be retitled “Betrayal After Betrayal”: under fascist pressure, clear-eyed rebels collapse again and again. Yet there’s still no alternative to resistance, Anderson insists, subtly shifting the story from political to lyrical.

Ultimately this remarkable film, equally (and often simultaneously) funny and serious, reveals itself to be about fatherhood rather than revolutionary terror. Fatherhood means responsibility, and it may seem that part of that duty is preparing your children for the next unwinnable battle. But the comfort for Bob — and for every worried dad — is that when it matters, the kids will figure it out themselves.