The horror franchise by director Danny Boyle and screenwriter Alex Garland now consists of four parts—the original 28 Days Later and a new trilogy: 28 Years Later, The Temple of Bones, and the third chapter, which we will most likely see next year (28 Weeks Later has been forgotten, as it has no connection to the universe).

All parts except The Temple of Bones were or will be filmed by Boyle himself, so the choice of director Nia DaCosta caused some concern. Her resume includes Candyman, Marvel, and the original Hedda, but even with such an impressive list, it was difficult to imagine whether the filmmaker would be able to carry on the legacy of the franchise. It was time to take a breath! DaCosta has made what is probably the harshest, most topical, bloodiest — and at the same time most hopeful and humane — installation in the series.

Although “28 Years Later” was a frightening story, it was nonetheless a warm tale of growing up and loss, which abruptly changes tone five minutes before the credits roll. Boyle introduced Jimmy and his “Jimmys” — characters with the style of Jimmy Savile, the emotional intelligence of Teletubbies, and a dose of good old ultraviolence in the spirit of A Clockwork Orange.

The Temple of Bones logically becomes the darkest part of the franchise, continuing the main idea of 28 Days Later: it’s not the infected that are scary, but the people you find yourself locked up with. Jimmy Crystal appears as a ruthless cult leader who kills for power and fun, but Nia DaCosta does not elevate his personality to an absolute, but changes the perspective, looking through the gold trinkets with an inverted cross straight into his soul, where she finds a frightened child embittered by his father. When his true nature is revealed, awe of the villain is replaced by disgust and sometimes contempt. The foundation of Jimmy’s cult - childhood illusions about an all-powerful father - Satan - collapses. And it turns out that the real power in infected England is not ultra-violence, but the good old “man needs man.” Not everyone who is capable of empathy will survive, but it is empathy that saves lost souls in the apocalypse created by humans. It is difficult to say whether this idea belongs to Alex Garland personally, but the film clearly reveals the sensitive soul and iron fist of Nia DaCosta, who reveals unexpected sides to the characters, clearly responding to the political climate of the present. Leaders like Elon Musk, rapidly rising podcasters, or even nationalist megachurches—all of them are surrounded by armies of aggressive fans and can also seem intimidating, waving chainsaws from the stage and wielding power—informational, political, or sentimental.

The Temple of Bones logically becomes the darkest part of the franchise, continuing the main idea of 28 Days Later: it’s not the infected that are scary, but the people you find yourself locked up with. Jimmy Crystal appears as a ruthless cult leader who kills for power and fun, but Nia DaCosta does not elevate his personality to an absolute, but changes the perspective, looking through the gold trinkets with an inverted cross straight into his soul, where she finds a frightened child embittered by his father. When his true nature is revealed, awe of the villain is replaced by disgust and sometimes contempt. The foundation of Jimmy’s cult - childhood illusions about an all-powerful father - Satan - collapses. And it turns out that the real power in infected England is not ultra-violence, but the good old “man needs man.” Not everyone who is capable of empathy will survive, but it is empathy that saves lost souls in the apocalypse created by humans. It is difficult to say whether this idea belongs to Alex Garland personally, but the film clearly reveals the sensitive soul and iron fist of Nia DaCosta, who reveals unexpected sides to the characters, clearly responding to the political climate of the present. Leaders like Elon Musk, rapidly rising podcasters, or even nationalist megachurches—all of them are surrounded by armies of aggressive fans and can also seem intimidating, waving chainsaws from the stage and wielding power—informational, political, or sentimental.

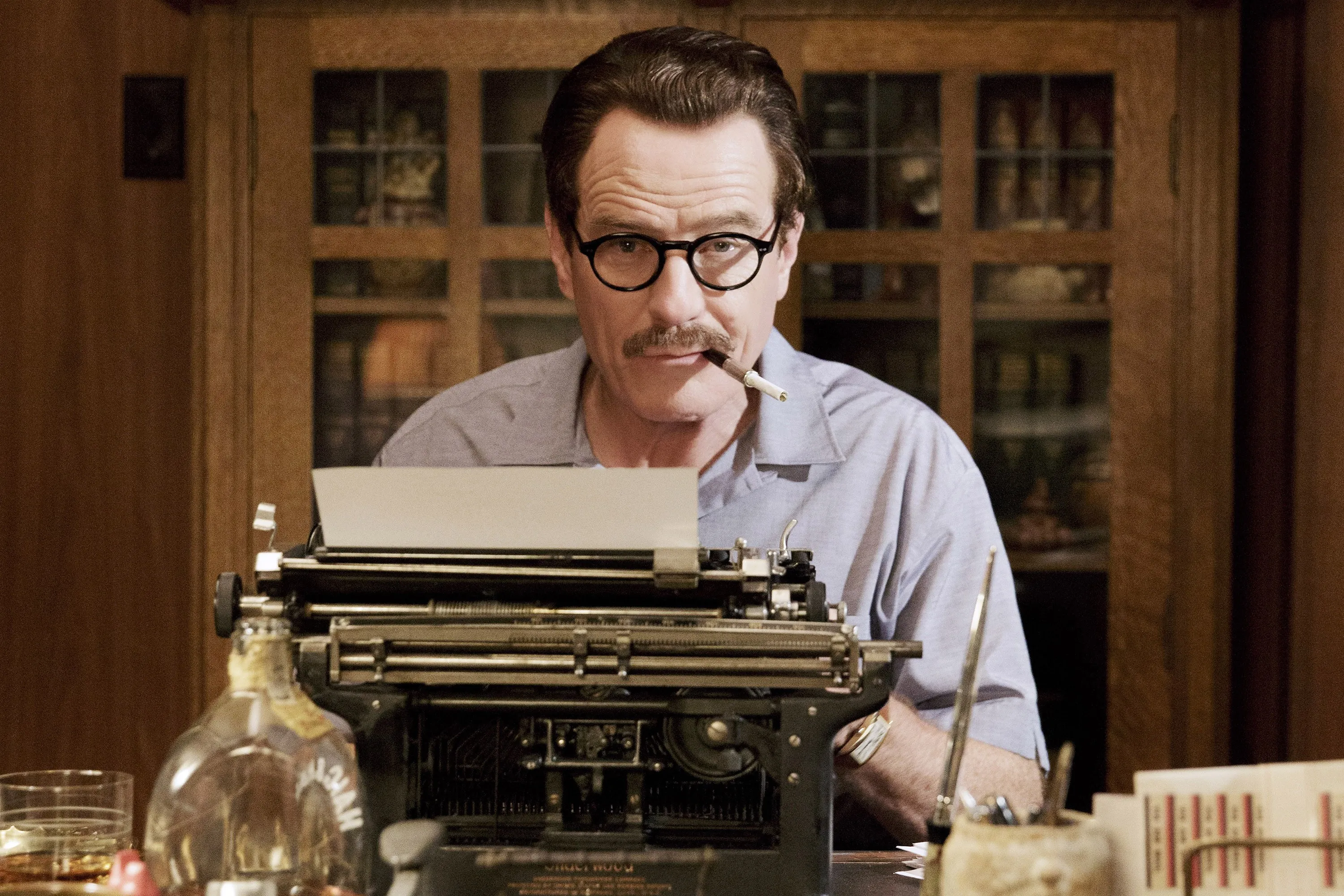

But the closer you look, the more obvious it becomes: all this power is based on one big illusion that could evaporate at any moment. The Temple of Bones places us at a crossroads between the cult of the individual and humanity, drawing attention to how one can erase the other and how easily each individual can fall victim to the phenomenon, finding themselves inside this bubble or under pressure. And where is the promised hope? In Dr. Ian Kelson’s arch.

While Jimmy terrorizes the neighborhood, Kelson tries to befriend Samson and tests all kinds of drugs on him to find a vaccine for the virus. Their connection with the alpha turns out to be unexpectedly touching and even funny — especially against the backdrop of mountains of bones and a meat grinder in the neighboring areas. Even in the most terrible times, salvation can only be found in each other or in an impromptu rock concert (yes, that’s in the movie too). The main thing is not to lose empathy and faith in the humanity of the person standing to your right. Even if he has a machete in his right hand. It might still come in handy.

While Jimmy terrorizes the neighborhood, Kelson tries to befriend Samson and tests all kinds of drugs on him to find a vaccine for the virus. Their connection with the alpha turns out to be unexpectedly touching and even funny — especially against the backdrop of mountains of bones and a meat grinder in the neighboring areas. Even in the most terrible times, salvation can only be found in each other or in an impromptu rock concert (yes, that’s in the movie too). The main thing is not to lose empathy and faith in the humanity of the person standing to your right. Even if he has a machete in his right hand. It might still come in handy.