“Eternity” arrives at a moment when debates around Celine Song’s “Past Lives” are still echoing online. That film split audiences into Team One Man and Team The Other, sparking endless arguments about gender roles, cultural differences and childhood trauma. “Eternity”, also released by A24, picks up that conversation but lowers the temperature, offering its own version of a romantic triangle: the idealized ex, the flawed but familiar husband, and a woman suspended between the life she lived and the one she once imagined.

Joan (Elizabeth Olsen) doesn’t yet know what awaits her in the afterlife, but the audience gets there quickly. An elderly married couple heads to a family gathering to find out whether they’re expecting a great‑granddaughter or great‑grandson. During dinner, Joan’s husband Larry (Miles Teller) chokes on a salted pretzel and dies — suddenly, almost absurdly, as if it were just another awkward moment at a family party.

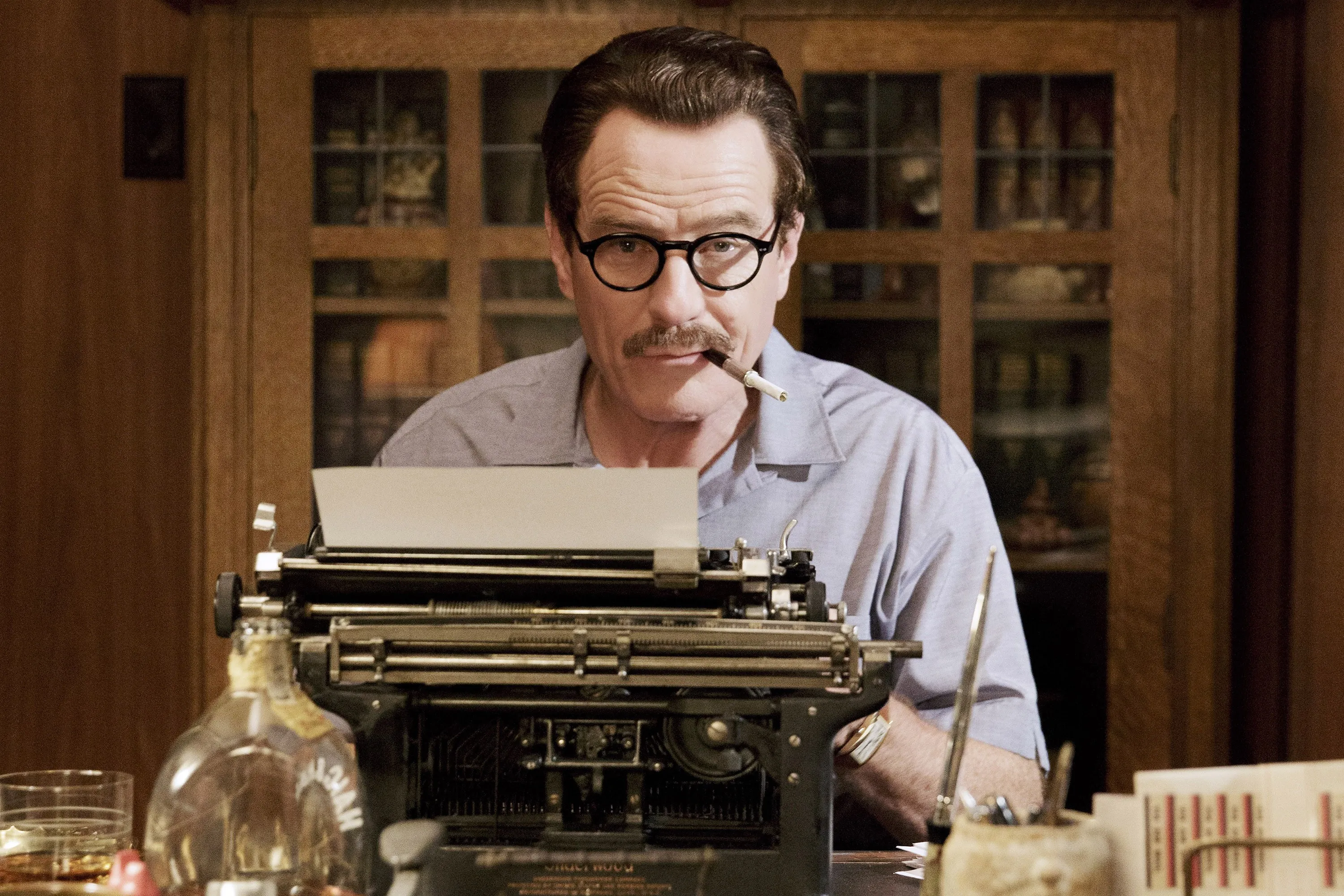

Instead of a tunnel of light, Larry wakes up in an overcrowded lobby where the dead are assigned personalized afterlife packages. Capitalism, the film suggests, has long since reached heaven too: now there’s “eternity for wizards”, a “beach eternity”, a “smokers’ eternity”, a “vampires’ eternity”, even an “eternity without men” — a catalog of forever that looks like a travel agency gone wild.

Larry has one week to pick his one‑way destination. But he is not ready to go anywhere without Joan, who is terminally ill and will soon join him on the other side. What he doesn’t realize is that someone has already been waiting for her there for 65 years: her first husband Luke (Callum Turner), killed in the Korean War and stuck in a stylish limbo, is determined not to lose her twice.

Director David Freyne (“Dating Amber”) plays with familiar afterlife tropes. Where films like “Ghost”, “What Dreams May Come” or “Just Like Heaven” treated death as an unbreakable barrier separating lovers, “Eternity” uses it as the starting point for a new love story. The limbo here looks like an endless 1960s conference center, and angels have been reimagined as afterlife consultants, handing out brochures and aggressively upselling their favorite versions of forever.

The world is deliberately artificial: the dead keep dyeing their hair, shaving, taking showers, changing outfits, slipping into depressive alcoholism or brief affairs. The only real rule is that no one goes back. Choosing a place and, more importantly, a partner for eternity becomes the film’s central moral challenge.

Joan is torn between the pristine memory of her first husband and the messy, lived‑in love she shares with Larry. Freyne watches the duel of male egos with a dry wit: both men are charming and ridiculous in equal measure, and their attempts to win Joan back only highlight that real growth belongs to the woman in the middle.

The consultants (a scene‑stealing pair played by Da’Vine Joy Randolph and John Early) act like overzealous sales reps and failed cupids at once. They meddle, offer misguided advice and keep pushing their own candidates, making every decision more complicated. Where “Past Lives” was about a heroine who couldn’t quite articulate what she wanted, “Eternity” insists that choosing one life always means letting go of countless hypothetical versions.

Freyne intentionally stretches the film’s second half, offering several almost‑endings and showing that none of them are perfectly satisfying. A bright but short‑lived romance, a steady partnership built over decades, compromise for someone else or for yourself — all of these options feel both right and incomplete. In the end, the film lands on a conclusion that is classically romantic, even conservative, but emotionally coherent: only the person who has learned to look beyond their own ego earns the right to love someone in life and in eternity.

“Eternity” is unlikely to redefine the rom‑com, but it fits neatly into the genre’s current revival with its mix of warmth, dark humor and gentle metaphysics. Among dozens of imagined afterlives, it quietly argues for one simple thing: the most precious life is the one in which you actually showed up, said what mattered and shared not just forever, but the everyday.