Guillermo del Toro needs no introduction: the Mexican filmmaker has long occupied his own niche in the world of cinema, having received both the Golden Lion and Oscars. His scary tales, whether “The Shape of Water” or “Pan’s Labyrinth,” often don’t frighten but make you cry, and homeless orphans invariably find their way home.

“Frankenstein” is not a new take on Universal’s classic horror film, but a free interpretation of Mary Shelley’s novel. The novelist’s book and Carlo Collodi’s fairy tale “Pinocchio” accompanied Guillermo from childhood and were on his bucket list — things to accomplish in life. The puppet animation came out three years ago, and now it’s time for “Frankenstein,” which touches the heart with its story of death.

From the first frame, the breath is taken away by the impregnability of snow-covered expanses: vast blocks of ice hang over sailors wrapped in tattered coats. The ship is frozen in northern waters, and Captain Anderson (Lars Mikkelsen) is destined to witness the meeting of a shaggy man with a cold heart (Oscar Isaac) and a frenzied monster (Jacob Elordi) — with an open soul and clenched fists.

The prologue gives way to two chapters — creation and farewell. In the first, a scientist obsessed with the idea of defeating death, Victor Frankenstein, experiments with eugenics and electricity. In the next, the Wonder born from experiments wants to learn to live and even love, but timid feelings toward the world around are doomed to be unrequited due to the external ugliness of a creature sewn together from other bodies.

For its scope — from life to death, from earth to the Moon, from hatred to love — del Toro’s “Frankenstein” wants to be immediately bathed in love and admiration. The large-scale and classic, or even old-fashioned, picture seems to carry you somewhere far, far away, to a not-so-distant past era when films seemed significant — both ideologically and even physically. The gothic novel elevated to blockbuster scale, the enchanting architecture of light and shadow, and Alexandre Desplat’s music are striking.

Jacob Elordi empathetically conveys the homelessness and orphanhood of the monster from the screen — goosebumps! The actor transforms his texture and outrageous beauty, naturally close to the perfection of ancient sculptures, into the frightening plasticity of a statue with a face disfigured by scars. The actor transforms into a completely special and unique creature — frightening and tender, wild and vulnerable, alive and dead.

Del Toro doesn’t follow the text too scrupulously, but carefully preserves the idea: as with “Pinocchio,” the director offers his own reading of a familiar story. Del Toro’s monsters have always deserved manifestations of humanism far more than humans: both the ghost of a dead boy in “The Devil’s Backbone” and the amphibian man in “The Shape of Water,” and now — as if the leader of all outcasts — Victor Frankenstein’s monster.

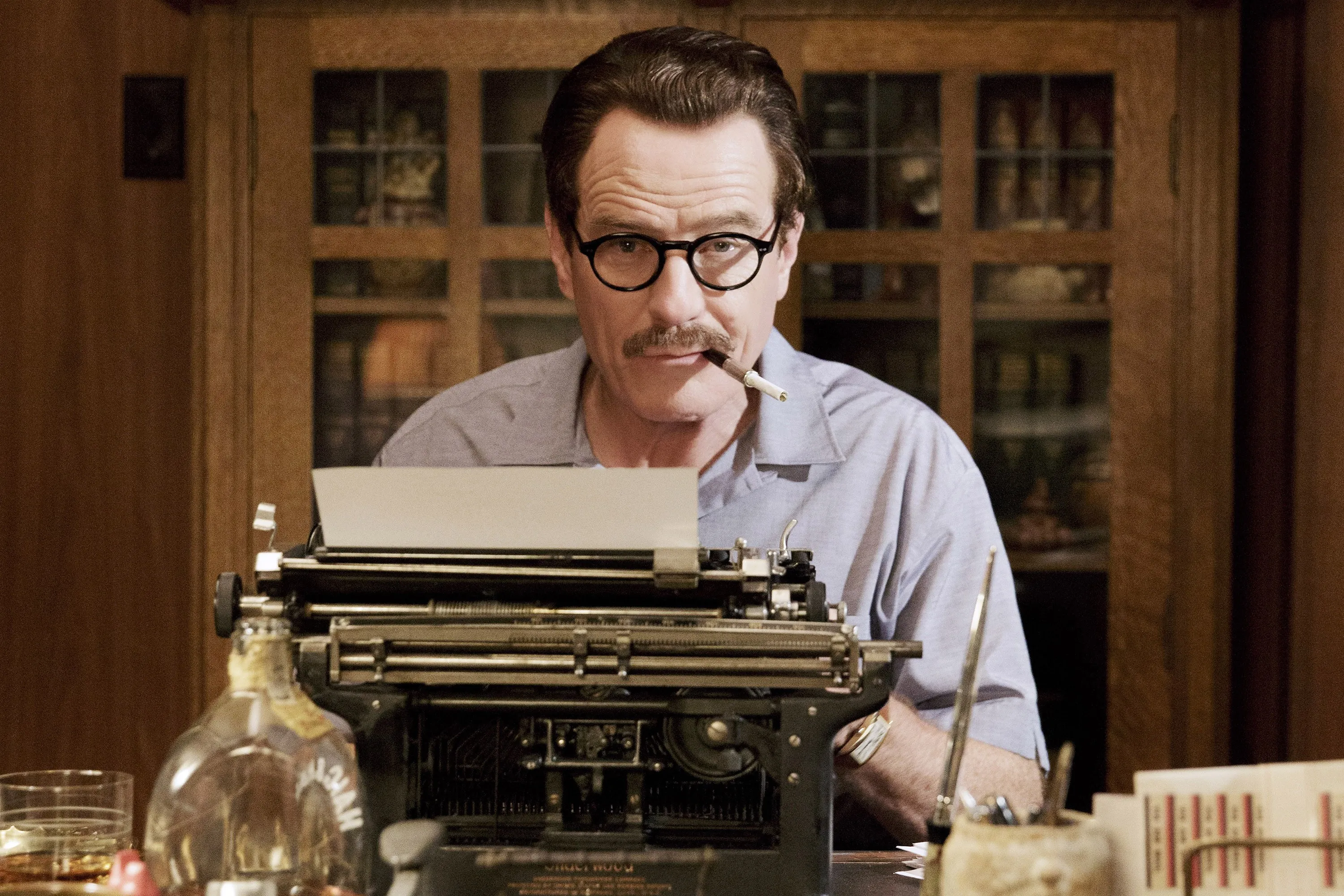

Of course, the most unpredictable and cruel creation turns out to be not the product of a visionary mind, but the possessor of ambitions to swap life and death. Oscar Isaac’s Victor Frankenstein is irresistible in his determination and repulsive in the vanity of a man who felt like a god. The main difference from Shelley’s novel is Victor’s biography: instead of a loving family, Victor got a tyrannical father, whose perfectionism, beaten into his son with rods, turns the offspring into the same domestic tyrant.

Kind people to the creation are random people who don’t stay long in its fate: a blind old man from a distant village (David Bradley) and Victor’s sister-in-law Elizabeth (Mia Goth). It is in the presence of a female figure nearby that one feels the kinship of the recluse with other great outcasts of the cinema world, like King Kong. Elordi’s Prometheus is like a general declaration of love to all orphans, outcasts, and unloved children, not accepted by the big world. Another del Toro fairy tale again teaches mercy and the ability to see beauty in any living being: every guest can become family in the house that Guillermo built.