The comedy genre is in decline — the industry has been saying this for years — and therefore eagerly devours every release that promises good humor. This time, the spotlight is on director and actor Aziz Ansari, who has already made a name for himself in comedy: he played Tom in the series Parks and Recreation and was also the showrunner for the sitcom Master of None, in which he played the lead role. In fact, we were supposed to see Ansari’s first film a couple of years ago, but something went wrong: during the filming of “Being Mortal,” a scandal erupted over the behavior of Bill Murray, who was involved in the project, and production was suspended. Ansari did not despair and decided to talk about capitalism, unemployment and unhappy lives. This is how “Good Fortune” came about, starring Keanu Reeves, Seth Rogen and Ansari himself in the lead roles.

Arj (Aziz Ansari) is a loser who sleeps in his own car and earns money doing one-off jobs that he finds on a special app for odd jobs. His life is worthless — Arj is absolutely sure of this, as he declares in his first meeting with the angel Gabriel (Keanu Reeves). The celestial being also has problems with his job: he is not allowed to move up the career ladder, and the only thing he does is save people from accidents while they are on their phones while driving. Gabriel dreams of saving a lost soul and finds it in Arj. The only one who has it all is Jeff (Seth Rogen), a typical tech bro and resident of an expensive penthouse, for whom Arj worked as an assistant for a couple of weeks before making a fatal mistake and losing his job. Gabriel decides to switch the men’s places so that Arj can see that rich people cry too. However, the plan does not work, and the once-poor hero has no intention of returning to his old life. “Good Fortune” could be called the Prince and the Pauper of the gig economy — it seems that everyone has come to terms with the fact that stable employment has become a myth, and constant side jobs are the new norm. This adaptation of Mark Twain’s classic work suddenly takes on a fresh perspective: while in the original version the characters were convinced that every social class has its own problems, in the new version it turns out that money really can buy happiness. Ansari cautiously approaches criticism of economic inequality, mentioning unfair pay and the absurdity of the tax system, but the satire does not go beyond a few isolated remarks. Perhaps this is because Ansari himself is quite far removed from the life of his own character — it is unlikely that a comedian with a contract with Netflix and a luxurious loft worth almost six million dollars remembers what poverty is like.

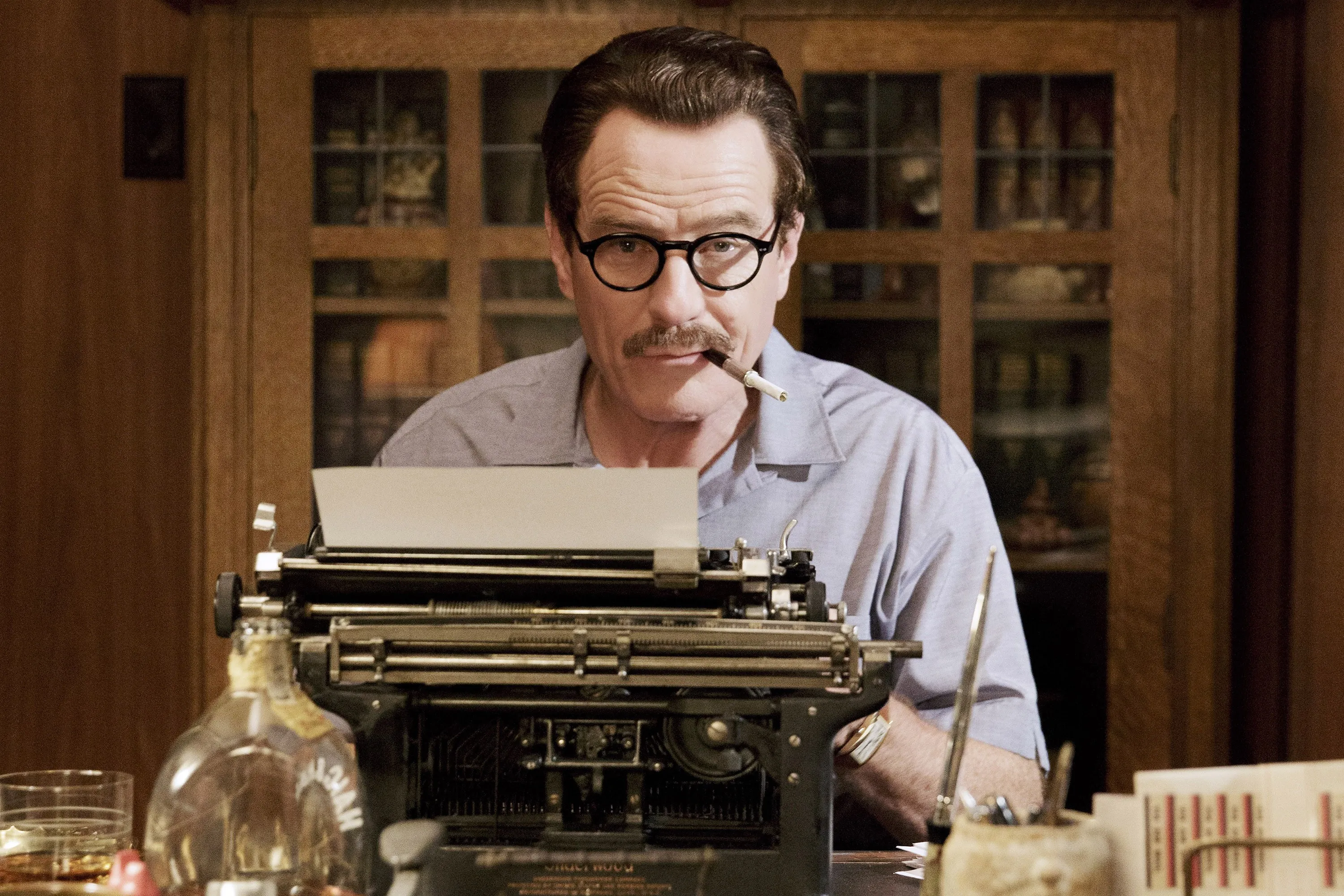

Ansari seems to be afraid to speak out about the real economic situation, and therefore decides to emphasize his directorial skills or highlight the acting power of Reeves and Rogen. The film vacillates between tones and visual styles: a comedy with grotesque gags suddenly gives way to an almost melancholic drama, then reverts back to farce, never lingering anywhere long enough. Good Fortune looks like a set of simultaneously solvable tasks: to show the director’s range, to give space to the stars, to speak out about inequality, and at the same time to remain a light-hearted attraction for the audience. Due to its internal restlessness, the film never forms a consistent point of view: none of the stated motifs — whether criticism of capitalism or a parable about compassion — becomes truly decisive. As a result, the film tries to do everything at once, but rarely allows itself to delve deeper — as if afraid of taking a wrong step and therefore preferring constant movement to a meaningful pause. The kaleidoscope of actors is both a plus and a minus for the film: each of the artists reveals their talent with dignity, but does not resonate with their colleagues, and a unified ensemble never forms. Reeves transforms the heavenly bureaucrat into a touchingly awkward observer of human life. Keanu’s character becomes the emotional center of the film: his transformation from a naive messenger into a man who learns about the world through work, cigarettes and cheap snacks is the film’s most accurate and humane observation. Ansari takes on his usual role of a confused hero — his Arj lives at the intersection of odd jobs and eternal fatigue, and the comedian feels confident in this role, although at times he seems too detached. Rogen, on the other hand, is organic in the role of a venture capitalist whose privilege remains caricatured throughout the film. Kiki Palmer brings liveliness to the film, playing an easy-going activist and founder of a warehouse workers’ union, while Sandra Oh, in the role of an angelic boss, adds irony, emphasizing that even in heaven there is a strict hierarchy. The different styles acting only reinforce the feeling of disjointedness — Rogen’s demonstrative eccentricity, Reeves’ deliberate stiffness and Ansari’s own pronounced insecurity seem to exist in parallel films.

Ultimately, Good Fortune sorely lacks coherence — and this is directly related to how many roles Ansari takes on at once. As a screenwriter, director, and lead actor, he seems to be scattered between tasks, preventing the story from coming together into a convincing and coherent statement. The film feels like a collection of separate comedic episodes, held together by situational jokes and the actors’ charisma, but not by an overall movement or internal logic. Perhaps Ansari should have taken a step back and focused on the story itself — giving it the attention it deserves, without trying to prove everything at once. Good Fortune is a neat, even cautious debut, with far more ambition than realized potential.