Cinema has long explored the theme of solitude and the connection between humans and nature. Directors like Ben Rivers show characters dissolving into landscapes, Denis Côté creates collective images of those who choose life outside society, and Chloé Zhao in “Nomadland” demonstrates how wandering can heal. Clint Bentley in “Train Dreams” continues this tradition, adding his own voice to it.

The story of Robert Grainier begins in 1893, when a seven-year-old boy arrives in the town of Fry, Idaho. Almost nothing is known about his past — his foster parents remain nameless, and his childhood passes in the company of forests and fields. Robert leaves school early to work as a fisherman, then becomes a lumberjack, participates in building a railway bridge. His life is filled with encounters with friends, sunrises and sunsets, seasonal work and returns home.

At home, his wife Gladys (Felicity Jones) and daughter Katie await him. Despite modest income, the family makes plans: to open a sawmill, to expand the farm. But suddenly tragedy strikes this small world, a tragedy that defies explanation. It weighs heavily on Robert’s shoulders, forcing him to gather the fragments of his former life and fruitlessly search for answers about the causes of what happened. The world continues to move forward, while the hero remains alone with his grief.

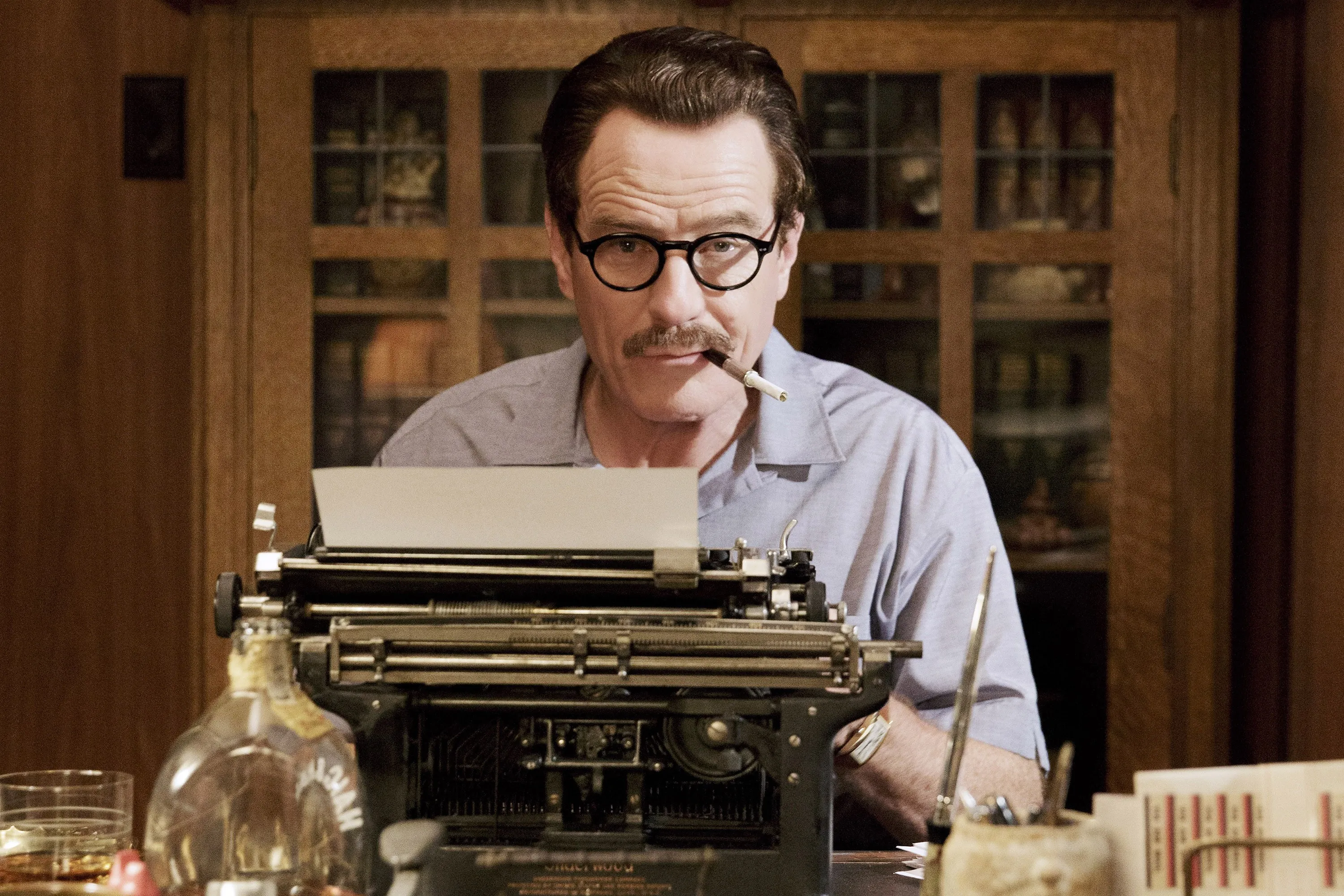

The film is based on a novella by Dennis Johnson, first published in 2002 in The Paris Review. A separate edition came out in 2011, and that same year the author became a Pulitzer finalist — the award was not given due to insufficient votes from the jury. Johnson turned the private story of a lumberjack into a large-scale testimony of an era, and Bentley, who had only made “Jockey” before, but already received an Oscar nomination for the screenplay of “Sing Sing” with Colman Domingo, approaches the material with caution. Together with Greg Kwedar, he creates a leisurely ballad about the transience of life.

The visual style of the film recalls the work of Terrence Malick: refined landscapes, thoughtful figures among wheat fields and in forest fog. Cinematographer Adolpho Veloso shoots the American Northwest as a living organism, where light seems to try to comfort the characters in moments of sorrow. The world changes, and Robert barely keeps up with these changes.

Faced with tragedy, the hero searches for answers in the past. Maybe he’s guilty because he didn’t stand up for a Chinese worker when racist colleagues took the law into their own hands? Or in childhood he should have shown more compassion to a dying man in the forest? Or maybe the desire to acquire a sawmill and never leave for shift work again was to blame? The film is not so much a linear biography as a photo album with randomly arranged snapshots: here’s Robert arriving in Fry as a child, here he gives a dying man a drink from his boot, here he meets a friend whom he will lose years later.

Edgerton’s hero wanders through forests, sleeps in temporary dwellings, encounters dogs and ghosts of the past, never ceasing to ask questions. The director weaves the human figure into greenish-brown tones of nature, making us admire the beauty of the world together with the episodic character William H. Macy. However, sometimes the image seems too polished for such a tender story — one wants to mute the colors and give the camera more freedom. While the visual remains within strict boundaries, the voice-over by Will Patton tells more than necessary. The desire to reflect the literary source is understandable, but the creators slightly overdo it with words — the story could exist on its own, through close-ups, the movement of foliage, panoramas of a changing world.

Despite these rough edges, “Train Dreams” is a rare success for Netflix, a film capable of attracting viewers of different generations. Johnson and Bentley speak of love and pain, of mortality and tragedies that cannot be prevented but can be survived. Of the fragility of memory and how even the most valuable will eventually turn to ash. Of how the living becomes part of the dead, and the dead — part of the living. Perhaps Nathan Fielder was right: peace can only be found in the sky, dissolving in the purity of flight, where pain, guilt, and the weight of years lived disappear, leaving only the lightness of the moment.