I can talk about “The Silence of the Lambs” for hours, but right now I want to focus on one thing — how ingeniously the film plays with the subjectivity of the gaze (put simply, whose eyes we look through and how we perceive what is happening on screen).

A dry clinical fact about the plot: one of the key storylines follows young FBI trainee Clarice Starling, who investigates a chain of murders while simultaneously trying to push through a male world that is openly hostile toward her.

The confrontation with that male environment is shown visually more than once — for example, in the elevator scene:

A minute of cinephile pedantry

There is a theory of the male gaze (part of the seminal essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”). The idea is straightforward: most films are made by men (directors, cinematographers, screenwriters), star men in the lead roles, and are watched primarily by men. Because of that, the camera’s point of view — the way we look at what’s happening — is usually male.

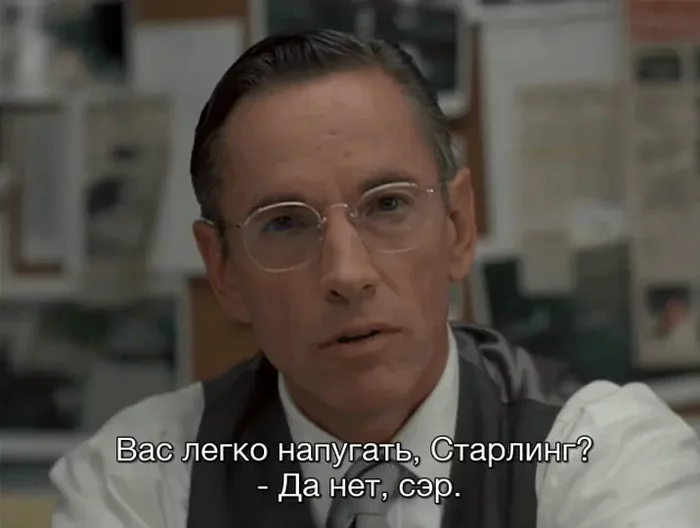

But “Silence of the Lambs” flips the theory on its head. If we normally watch films from a male viewpoint, here the film itself looks back at us with that same male gaze, forcing us to feel maximum discomfort. This is most noticeable in the dialogue scenes.

Usually, when someone speaks in a movie, they look slightly past the camera. A canonical example of this geometry from “Pulp Fiction”:

In “Silence,” it works differently — characters look straight into the camera, literally at us (and often from a closer angle than necessary).

The result is that we experience everything through the eyes of an inexperienced rookie agent. The entire male/female dualism is also evident in the standoff between Clarice and Buffalo Bill: Clarice tries to claim a traditionally male role, while Bill, on the contrary, longs for a female one.

There is only one subjective point of view in the film besides Clarice’s — when we see the victims through Buffalo Bill’s eyes. The killer objectifies women as much as possible; they are merely raw material (he doesn’t even call them by name, referring to them in the third person).

That creates a sharp contrast: in Clarice’s scenes, the camera sees the world like a young woman, while in Bill’s scenes we stare at those young women through the eyes of a predator. The final confrontation becomes the culmination. It’s a reinterpretation of the Final Girl trope: instead of the usual victim’s perspective, we suddenly look through the killer’s eyes, and in order to win Clarice literally has to feel that oppressive male gaze coming from us, the audience — and she manages to do it.

About other visual techniques

It’s also worth highlighting how the cinematographer works with push-ins. This is especially vivid in the last dialogue between Hannibal and Clarice (it’s impossible to discuss this film without mentioning Lecter 🙂). With every line his face moves closer until the bars of the cell disappear from view.

Finally, I adore the metaphor in this shot from the ending:

The fluffy white dog in the rescued girl’s arms is the embodiment of those lambs from Clarice’s nightmares — the ones she failed to save in childhood but is finally able to save now. And in the last shot the dog — the lamb — is quiet at last.